In the museum world, provenance is essential. Objects without a history are lost over time, orphaned by chance and lack of documentation. Sometimes, the information embedded in the piece itself is enough to secure its protection as a cultural relic, despite the loss of human information.

Archeologists, curators, and other professionals bemoan such disconnects: Simply put, objects outlive their owners or become separated from them. All too often, they float incognito in antique shops, resale stores, and yard sales, seldom rediscovered except by those who sense their significance and pursue it.

The ability to tie an object to its history is a connecting link between the past and present. Whether it’s in a museum collection, the media, or someone’s home, what we as humans really want is a story.

Who made it? How? What was its purpose? No matter what an object may be, it undeniably carries different meanings to different people: One person’s passion for vintage stoneware jugs equals another person’s love of first edition books or stamps. The story below concerns sentimental objects within families and the occasional miracles surrounding them, and this writer saw it unfold.

Johannes Jacubus van den Heuvel, born in August 1914, was the son of a Dutch cabinet maker. He apprenticed to his father at a young age in the time-honored way by sweeping the floors, completing the apprenticeship in six years. He married and became a father as World War II came to the Netherlands. After the rigors of war and German occupation in Rotterdam, Jan and his wife Cora decided to risk coming to America to give their six children a better life. He dropped the “van den” as too confusing for Americans unused to Dutch names, and the family name became Heuvel.

Jan’s craftsmanship dictated his path as a journeyman in the Cabinet Maker’s Shop at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in the mid-1950s. By 1959 he was the master cabinet maker, demonstrating 18th-century methods of furniture design and construction as well as training others. For three decades until his retirement in 1979, Jan crafted pieces as small as candlesticks or as large as the immense wooden corkscrew turning the press in the Printer’s Shop. In between were pieces such as his replica of the original Speaker’s Chair in the Virginia House of Burgesses, which now resides in the Virginia State Capitol.

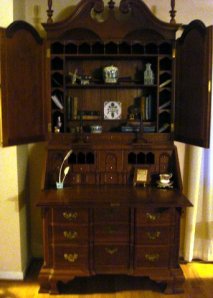

Some of Jan’s pieces were given to VIPs visiting Colonial Williamsburg, including heads of state. Some were purchased by collectors like famed news anchor Walter Cronkite, with major pieces valued at thousands of dollars. Among the most expensive were several secretary desks in the Chippendale style, each purchased by collectors outside of Virginia.

Making such fine reproductions was time-consuming; Jan took years to complete them. It entailed corresponding with the collector-customers, considering the fine details of design and scale with them, and becoming part of their lives in a unique way.

Johannes "Jan" Heuvel

One of these pieces was a Chippendale secretary of cherry wood made in a modified Rhode Island style. Jan was meticulous, even considering the room dimensions in 20th-century homes versus those of the 18 century (typically larger for the grander lifestyle of a gentleman desiring such furniture). Commissioned in 1962 by a Columbus, Ohio physician and his wife, the piece took years to make; the family visited Williamsburg in the summers to see the work in progress and took pictures. Jan delivered the desk personally in 1969 to Columbus, where it stayed until Spring 2011.

One daughter helping with her mother’s move out-of-state sought a new home for this piece. An earlier generation of her family had also been cabinet makers in the German tradition; she and her mother wanted the desk to be cherished for its intricate shell carvings, finely made dovetails, and elegant design, as it had been used and valued for over 40 years.

But where? Could it perhaps be reunited with its maker? Calling the Cabinet Maker’s Shop in Williamsburg revealed that one of Jan Heuvel’s sons still lived in Williamsburg, although his father had passed away in 2003 at age 88.

The next phone call sent news travelling from Williamsburg to North Carolina, Maryland, and Michigan, as family members heard the news. By July, the desk had a new home six miles from its starting point. It has connected two households and arrived within two weeks of the birth of Jan Heuvel’s latest great-grandson. Since then, three generations of Heuvel men — from 61 to newborn — have posed in front of this desk that each will own in turn.

That photo and others have been sent to the previous owner’s family in a flow of emails and phone calls. It has been more of an adoption than a transaction. Family members and friends have traveled from out-of-state to see the secretary, taking photos as a reminder of Jan’s artistry and the man himself.

At any point, the fragile trail from maker to object could have snapped. This desk could have been just another piece on the auction block or in a consignment shop. That it did not is a lesson in life, friendship, and the power of provenance.

I would like to speak with whomever wrote this article. I understand that Jan Heuvel made three of these Secretaries, I happen to know where the third one is.